I've been remiss in reposting articles here ever since I started using Facebook, so here's some things I've been reading lately:

First of all, I'm not a big fan of Tumblr - it often seems to be the worst kind of social media: no original content or even your own thoughts, just reposting, BUT, these, these I approve of:

Dads are the Original Hipster

And Hipster Animals:

Then, some feminism related links:

Poor Jane’s Almanac

By JILL LEPORE

The New York Times

Cambridge, Mass.

THE House Budget Committee chairman, Paul D. Ryan, a Republican from Wisconsin, announced his party’s new economic plan this month. It’s called “The Path to Prosperity,” a nod to an essay Benjamin Franklin once wrote, called “The Way to Wealth.”

Franklin, who’s on the $100 bill, was the youngest of 10 sons. Nowhere on any legal tender is his sister Jane, the youngest of seven daughters; she never traveled the way to wealth. He was born in 1706, she in 1712. Their father was a Boston candle-maker, scraping by. Massachusetts’ Poor Law required teaching boys to write; the mandate for girls ended at reading. Benny went to school for just two years; Jenny never went at all.

Their lives tell an 18th-century tale of two Americas. Against poverty and ignorance, Franklin prevailed; his sister did not.

At 17, he ran away from home. At 15, she married: she was probably pregnant, as were, at the time, a third of all brides. She and her brother wrote to each other all their lives: they were each other’s dearest friends. (He wrote more letters to her than to anyone.) His letters are learned, warm, funny, delightful; hers are misspelled, fretful and full of sorrow. “Nothing but troble can you her from me,” she warned. It’s extraordinary that she could write at all.

“I have such a Poor Fackulty at making Leters,” she confessed.

He would have none of it. “Is there not a little Affectation in your Apology for the Incorrectness of your Writing?” he teased. “Perhaps it is rather fishing for commendation. You write better, in my Opinion, than most American Women.” He was, sadly, right.

She had one child after another; her husband, a saddler named Edward Mecom, grew ill, and may have lost his mind, as, most certainly, did two of her sons. She struggled, and failed, to keep them out of debtors’ prison, the almshouse, asylums. She took in boarders; she sewed bonnets. She had not a moment’s rest.

And still, she thirsted for knowledge. “I Read as much as I Dare,” she confided to her brother. She once asked him for a copy of “all the Political pieces” he had ever written. “I could as easily make a collection for you of all the past parings of my nails,” he joked. He sent her what he could; she read it all. But there was no way out.

They left very different paper trails. He wrote the story of his life, stirring and wry — the most important autobiography ever written. She wrote 14 pages of what she called her “Book of Ages.” It isn’t an autobiography; it is, instead, a litany of grief, a history, in brief, of a life lived rags to rags.

It begins: “Josiah Mecom their first Born on Wednesday June the 4: 1729 and Died May the 18-1730.” Each page records another heartbreak. “Died my Dear & Beloved Daughter Polly Mecom,” she wrote one dreadful day, adding, “The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away oh may I never be so Rebelious as to Refuse Acquesing & saying from my hart Blessed be the Name of the Lord.”

Jane Mecom had 12 children; she buried 11. And then, she put down her pen.

Today, two and a half centuries later, the nation’s bookshelves sag with doorstop biographies of the founders; Tea Partiers dressed as Benjamin Franklin call for an end to social services for the poor; and the “Path to Prosperity” urges a return to “America’s founding ideals of liberty, limited government and equality under the rule of law.” But the story of Jane Mecom is a reminder that, especially for women, escaping poverty has always depended on the opportunity for an education and the ability to control the size of their families.

The latest budget reduces financing for Planned Parenthood, for public education and even for the study of history. At one point in the budget discussion, all money for Teaching American History, a federal program offering training to K-12 history teachers, was eliminated. Are we never to study the book of ages?

On July 4, 1786, when Jane Mecom was 74, she thought about the path to prosperity. It was the nation’s 10th birthday. She had been reading a book by the Englishman Richard Price. “Dr Price,” she wrote to her brother, “thinks Thousands of Boyles Clarks and Newtons have Probably been lost to the world, and lived and died in Ignorance and meanness, merely for want of being Placed in favourable Situations, and Injoying Proper Advantages.” And then she reminded her brother, gently, of something that he knew, and she knew, about the world in which they lived: “Very few is able to beat thro all Impedements and Arive to any Grat Degre of superiority in Understanding.”

That world was changing. In 1789, Boston for the first time, allowed girls to attend public schools. The fertility rate began declining. The American Revolution made possible a new world, a world of fewer obstacles, a world with a promise of equality. That required — and still requires — sympathy.

Benjamin Franklin died in Philadelphia in 1790, at the age of 84. In his will, he left Jane the house in which she lived. And then he made another bequest, more lasting: he gave one hundred pounds to the public schools of Boston.

Jane Mecom died in that house in 1794. Later, during a political moment much like this one, when American politics was animated by self-serving invocations of the founders, her house was demolished to make room for a memorial to Paul Revere.

Jill Lepore, a professor of American history at Harvard, is the author of “The Whites of Their Eyes: The Tea Party’s Revolution and the Battle Over American History.”

Dallas Sports Columnist Displeased With Pitcher’s Decision To Do A Totally Normal Thing

It can be hard to tell that Dallas Observer sports blogger Richie Whitt is a sports blogger, since his professional blog, the one that is actually hosted on Village Voice servers, largely consists of pictures of women in various states of undress and reflections on recent Korn performances, so you could be forgiven for wondering where the hell he thinks he gets off shitting on Texas Rangers pitcher Colby Lewis for having the gall to miss a start in favor of attending the birth of his second child.

I mean, my first question was, what is Richie Whitt doing writing about sports, anyway? Is there not a wet t-shirt somewhere in the whole of suburban North Texas that needs his undivided attention?

Apparently not. No, when Whitt heard that Colby Lewis skipped a game, well, this:

In Game 2, Colby Lewis is scheduled to start after missing his last regular turn in the rotation because — I’m not making this up — his wife, Jenny, was giving birth in California. To the couple’s second child.

That’s right, folks. If you can believe it, this guy attended the birth of his child. Take a moment to collect yourselves if you must. I know news like this can be hard to process. Ok? Ok.

And lest you think that Whitt was just joking, I invite you to read further, wherein Whitt doesn’t really joke at all but just talks about how hard it is for him to wrap his mind around the idea of taking a day off to see your kid born.

Don’t have kids of my own but I raised a step-son for eight years. I know all about sacrifice and love and how great children are.

But a pitcher missing one of maybe 30 starts? And it’s all kosher because of Major League Baseball’s new paternity leave rule?

Follow me this way to some confusion.

Imagine if Jason Witten missed a game to attend the birth of a child. It’s just, I dunno, weird. Wrong even.

See, it’s not that childless, single Whitt doesn’t know all about children and family sacrifice, it’s just that another dude choosing a different path than his is too hard for him to understand, and therefore wrong. No doubt the Gender Police have given Whitt some kind of very meaningful commendation (gilt mud tires, maybe!) and are preparing for quite the promotion ceremony.

Here’s where shit gets real: as the confused and disappointed Whitt noted, Colby Lewis is the first MLB baseball player to ever go on the league’s paternity leave list. This is not a small deal. This is a huge deal. This is a deal where a major sports operation moves from saying, hey dudes, we will pay you gazillions of dollars to chase a ball around a field and kids will look up to you for that as a role model, to saying hey dudes, with our express permission, how about you go be a father if you want to, because that is a good thing to do, that is also a role model thing to do. And Colby Lewis took them up on that. He decided that being a dad is important to him. And he went and was a dad and a husband and a partner.

And what’s more: he came back to work and is still a pretty fucking good baseball player.

So we can shrug off Whitt and say he’s just being a shit-stirring media personality who thinks any attention is good attention, which I am definitely doing, and which I think is a reasonable thing to do. But we need to go a step further and call out Whitt for using his shock-jock personality to perpetuate a system of toxic masculinity wherein men are only real dudes if they don’t do too much of that being-a-human-being shit, like trying to physically and emotionally support their families, witness once-in-a-lifetime moments and demonstrate that there’s more to life than a paycheck. Toxic masculinity, gender policing and shaming doesn’t just hurt women. Doesn’t just hurt men. Hurts everyone. Hurts families. Hurts people, all people, who deserve to not be pigeonholed and socially pressured into any one kind of behavior based on the junk in their drawers.

With this column, Whitt really hits the Toxic Masculinity Trifecta: ignorance (caveman too stupid to understand things other than sports/beer), fear (caveman cowed by freaky, unwelcoming ladybits and operations thereof) and dick-centricity (caveman judge value of all behavior in light of adherence to other socially constructed, traditionally male behavior). But hey, no doubt Whitt is pretty pleased at all the attention this is getting, not to mention the page views, because hey, page views you guys! It’s basically like thinking up a new cat meme! Victimless crime!

Except this kind of horsesassery isn’t a victimless crime at all. I don’t know if you guys look forward to this, or if Richie Whitt looks forward to this, but I do look forward to it: a day when those who have the microphone do not casually and ignorantly reinforce systems of gendered oppression that have been fucking up people’s shit for an awfully long time. Or maybe I’m wrong. Maybe being a father is the worst, and mocking men for doing absolutely, totally hetero-normal family stuff is super classy and awesome. I may have missed that memo because I was busy being parented by a loving father before growing up to watch many of my guy friends become great parents, because again, that is a normal and acceptable thing dudes do.

Of course, it’s interesting to observe the point at which Whitt, champion of toxic masculinity if ever there was one, felt it was reasonable and/or funny to call it “wrong” when a guy has demonstrably done the most heteronormative thing possible, which is to make a baby with a lady. Whitt doesn’t mind kids and family, ya know, he’s totally cool with that–it’s just that he wants to make sure the kids and family don’t upset some abstract image of Studly Professional Athlete, who is the epitome of manliness and would never let anything as silly–and unmanly–as parenting get in the way of actual priorities, like a baseball game. (And an individual baseball game as priority is up for serious debate, anyway, so go read Jason Heid’s post on Frontburner for more on why it’s not that big of a freaking deal if Lewis misses one game out of 30.)

So it’s really very simple: by choosing his family over his job, Colby Lewis is not performing masculinity properly, and that scares the shit out of people who have invested their entire careers, even their whole identities, in reinforcing said masculinity. What do I mean when I say a super studly professional athlete is not performing masculinity properly? I mean this: Colby Lewis’ act of choosing to be at the birth of his kid rather than starting as pitcher in a major league baseball game is a direct and public challenge to the patriarchal norm which dictates that women will be the ones to make career sacrifices, full stop. < / getting all women’s studies 101 on your asses >

Now, Whitt and his fans, one or both or all of whom I expect to turn up here in the comments section at any moment (oh, how I hope to hear a new sandwich-kitchen-stove joke, or perhaps a lengthy inquiry into whether I am fat, ugly or slutty!) probably think this all sounds like a bunch of feminist hoo-hah. It it totally is. Because feminism is for dudes, y’all. Richie Whitt just proved it.

Academia related links:

April 24, 2011

Paranoid? You Must Be a Grad Student

By Don Troop

Memo to grad students: Just because you're paranoid doesn't mean they're not about to give you a Ph.D.

A mild case of paranoia might even help you navigate the tricky path to that terminal degree, says Roderick M. Kramer, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford University's Graduate School of Business.

It's an academic cliché that graduate students are paranoid, but Mr. Kramer has actually crafted a linear model to explain it. The model depicts how factors common to the graduate-school experience—like being a newcomer unsure of your standing, and knowing that you're being sized up constantly—can ultimately induce social paranoia, a heightened sensitivity to what you imagine others might be thinking about you.

"That self-consciousness translates into a tendency to be extra vigilant and maybe overprocess information on how you're treated," Mr. Kramer says. (He published his model in a 1998 paper, "Paranoid Cognition in Social Systems.")

To be clear, he is not talking about clinical paranoia, an illness he studied at the University of California at Los Angeles under the psychiatrist Kenneth Colby, who had developed a computerized paranoid schizophrenic called PARRY. And Mr. Kramer, who has written extensively on the social psychology of trust and distrust, doesn't regard social paranoia as a pejorative term, either.

"It's meant to be almost a playful label to help people remember the consequences of being in these situations," he says.

Not only does he know what you're thinking, but he also knows why. Roderick M. Kramer has developed a linear model to explain the type of social paranoia common to graduate students.

Academe, says the cartoonist Jorge Cham, is an ego-driven industry where perception is everything and weakness is perceived as a character flaw.

Mr. Cham abandoned his own academic career as a robotics researcher six years ago to draw his comic-strip parody of grad-school life, Piled Higher and Deeper.

"It's competitive, so people are very afraid of admitting that they're having trouble with their research, or that they're having trouble getting data, or that maybe they need to rethink their hypotheses," says Mr. Cham. That often means that the people best positioned to help a grad student resolve a particular dilemma—the adviser and members of the cohort—are the last ones the student will go to for help.

In spite of the accomplishments listed on their CV's, Mr. Cham says that grad students sometimes pull him aside and privately admit feeling like "they're somehow not smart enough or that they're fooling people—that they feel like impostors."

The students interviewed for this article raised that theme more than once. Anxiety about their standing seemed to vary depending on details like gender, field of study, fellow students' collegiality, and the adviser's attentiveness. The biggest variable, of course, was the student.

"I've never presented a project that I haven't felt like my peers or my faculty would find outstanding because I'm so nervous about being judged harshly," says a graduate student in anthropology at a large state university in the South. Though her adviser is warm and supportive and her fellow-grad students are friendly, she routinely hears them criticizing presentations by scholars from other universities after academic conferences. "The last thing you want to do is be on the other end of that stick," says the student, who describes scholarly research and presentation as an "academic performance" with its own precise language and exacting standards.

And as a woman in science she is up against what Mr. Kramer says is one of the primary antecedents to grad-student paranoia: the feeling of being socially distinct—a token. "I'm constantly curious about whether I'm being taken seriously," she says. "I'm very aware of hemlines, how much my neckline plummets, if I'm wearing too much makeup."

Like most graduate students interviewed for this article, she agreed to speak only if guaranteed anonymity. Does that sound a little paranoid? Mr. Kramer might deem it wise. A mild social paranoia can actually be helpful, he says, because it can trigger the types of "prudent and adaptive" behaviors that the anthropology student described, like adjusting your speech or appearance to fit in. It might also cause you not to want a reporter to use your name when you reveal that sometimes you feel a little paranoid.

Paranoia has its Pluses

Bradley Ricca earned his doctorate in 2003 from Case Western Reserve University, where today he is a lecturer in English. He recalls experiencing his own adaptive response to grad-student paranoia while preparing for his comprehensive exams. Mr. Ricca, who had been given two questions to study, got word that a friend who was also taking the exams was poised to set the curve.

"I heard that he had not only already written extensive outlines and copy for his answers, but he had footnoted them as well," Mr. Ricca wrote in an e-mail describing the incident. "I froze in my Doc Martens."

Mr. Ricca skipped sleep for nearly a week, writing out his answers and footnoting them. Both men passed their comps, and while Mr. Ricca never did find out whether the rumor about his friend was true, he credits "the paranoia inherent in English departments" with motivating him to study harder.

"English studies seems, to me, a culture laced with paranoia," Mr. Ricca says. "Where are the jobs? Where is the funding? What are we doing this decade?"

People who work in creative programs often suffer the worst from social paranoia, says Mr. Kramer, who began his own academic career as an English major aspiring to publish novels and screenplays.

"The more subjective the enterprise, the more uncertainty about the evaluative standard, the easier it is to overprocess information," he says. "You don't have that objective reference."

One former graduate student in a "cutthroat writing program" sums it up: "When someone criticizes your poem, you think, 'Why do they hate me so much?'"

Mr. Kramer says it's up to good doctoral advisers to minimize that dysfunctional suspicion. "They should stay in touch with their students. They should give them regular feedback that lets them know where they stand—not false feedback to make them unduly optimistic—but realistic feedback."

A female graduate of a different writing program—one where the cohort was much younger than she was and the faculty largely male and unsupportive—credits her survival to valuable mentoring from a new (male) faculty member who wasn't part of the old guard. She also followed the advice of a more senior grad student: "Invest your ego somewhere else and find some support system that's separate from this program—your family, your lover, or whoever."

In her case, the woman bonded with a fellow student who was also in her late 20s, and the two women helped each other gauge when their peers' criticisms were valid and when they were simply rooted in competition.

Such social support systems are a "very adaptive, healthy strategy that reduces uncertainty about your standing," Mr. Kramer says.

But a graduate student in clinical psychology at a public university in the Northeast says he's seen problems result when people try to function as both confidant and classmate.

"Business and pleasure often get mixed together when you're working 80 hours a week and you spend 90 percent of your waking moments with the same people," he says. "You really rely on these people to satisfy multiple roles, and trying to maintain these things certainly can ramp up the anxiety."

Also muddying his department's mental-health waters, he says, is that clinical psychologists sometimes take on some of the characteristics of the patients they work with.

"There might be a bit of an overrepresentation in terms of how people tend to express themselves, just given the content of what we study," he says.

"We tend to adopt the mind-set of those we're trying to conceptualize."

Adding to the anxiety, he says, are the same things that his peers in other disciplines worry about, like whether they're successfully evolving from students into professionals, and whether the gamble of grad school will pay off financially.

"I'm aware of people experiencing symptoms of paranoia or this feeling of disassociating when they're under heightened anxiety for prolonged periods of time, which seems to be the definition, in many ways, of graduate school," he says.

Sometimes, he says, the pressure students feel to demonstrate their mastery of the subject to professors comes at the expense of relationships with their peers. He's even seen students confront one another for talking too loudly or in other ways overshadowing their classmates.

A medical student at the same Northeast institution admits that he and others spend a disproportionate amount of time mulling how to impress their professors in hopes of getting favorable letters of recommendation for their residency applications.

On rotations they may work with a particular professor for only three or four weeks, a short time "to demonstrate that we're personable and that we have the knowledge they demand from us," he says. Grad students feel they must keep themselves at the fore of their professors' minds.

In truth, Mr. Kramer says, most faculty members don't actually spend much time thinking about their graduate students. In a study published in 1996, he found that graduate students estimated that their professors spent 32.4 minutes a week ruminating on their individual faculty-student relationships. The professors estimated that it was more like 10 minutes. Mr. Kramer speculates that, because self-reported data are notoriously unreliable, the actual difference is even greater.

When he meets former students at Stanford alumni events, he says by way of example, many of them remain self-conscious about middling grades they made in his classes 10 or 15 years earlier.

"They're processing the whole thing in terms of this evaluation that took place 10 years ago, and for me it's not even a memory," he says.

They needn't feel paranoid, says Mr. Kramer. Really, he's just glad to see them.

Professor Deeply Hurt by Student's Evaluation

The Onion, APRIL 2, 1996

Leon Rothberg, Ph.D., a 58-year-old professor of English Literature at Ohio State University, was shocked and saddened Monday after receiving a sub-par mid-semester evaluation from freshman student Chad Berner. The circles labeled 4 and 5 on the Scan-Tron form were predominantly filled in, placing Rothberg’s teaching skill in the “below average” to “poor” range.

English professor Dr. Leon Rothberg, though hurt by evaluations that pointed out the little globule of spit that sometimes forms between his lips, was most upset at being called "totally lame" in one freshman's write-in comments.

Although the evaluation has deeply hurt Rothberg’s feelings, Berner defended his judgment at a press conference yesterday.

“That class is totally boring,” said Berner, one of 342 students in Rothberg’s introductory English 161 class. “When I go, I have to read the school paper to keep from falling asleep. One of my brothers does a comic strip called ‘The Booze Brothers.’ It’s awesome.”

The poor rating has left Rothberg, a Rhodes Scholar, distraught and doubting his ability to teach effectively at the university level.

“Maybe I’m just no good at this job,” said Rothberg, recipient of the 1993 Jean-Foucault Lacan award from the University of Chicago for his paper on public/private feminist deconstructive discourse in the early narratives of Catherine of Siena. “Chad’s right. I am totally boring.”

In the wake of the evaluation, Rothberg is considering canceling his fall sabbatical to the University of Geneva, where he is slated to serve as a Henri Bynum-Derridas Visiting Scholar. Instead, Rothberg may take a rudimentary public speaking course as well as offer his services to students like Berner, should they desire personal tutoring.

“The needs of my first-year students come well before any prestigious personal awards offered to me by international academic assemblies,” Rothberg said. “After all, I have dedicated my life to the pursuit of knowledge, and to imparting it to those who are coming after me. I know that’s why these students are here, so I owe it to them.”

Though Rothberg, noted author of The Violent Body: Marxist Roots of Postmodern Homoerotic Mysticism and the Feminine Form in St. Augustine’s Confessions, has attempted to contact Berner numerous times by telephone, Berner has not returned his calls, leading Rothberg to believe that Berner is serious in his condemnation of the professor.

“I’m always stoned when he calls, so I let the answering machine pick it up,” said Berner, who maintains a steady 2.3 GPA. “My roommate just got this new bong that totally kicks ass. We call it Sky Lab.”

Those close to Rothberg agree that the negative evaluation is difficult to overcome.

“Richard is trying to keep a stiff upper lip around his colleagues, but I know he’s taking it very hard,” said Susan Feinstein-Rothberg, a fellow English professor and Rothberg’s wife of 29 years. “He knows that students like Chad deserve better.”

When told of Rothberg’s thoughts of quitting, Berner became angry.

“He’d better finish up the class,” Berner said. “I need those three humanities credits to be eligible to apply to the business school next year.”

The English Department administration at Ohio State is taking a hard look at Rothberg’s performance in the wake of Berner’s poor evaluation.

“Students and the enormous revenue they bring in to our institution are a more valued commodity to us than faculty,” Dean James Hewitt said. “Although Rothberg is a distinguished, tenured professor with countless academic credentials and knowledge of 21 modern and ancient languages, there is absolutely no excuse for his boring Chad with his lectures. Chad must be entertained at all costs.”

A really great article on politics, science, and psychology: The Science of Why We Don't Believe Science

How our brains fool us on climate, creationism, and the vaccine-autism link.

By Chris Mooney, Mother Jones

"A MAN WITH A CONVICTION is a hard man to change. Tell him you disagree and he turns away. Show him facts or figures and he questions your sources. Appeal to logic and he fails to see your point." So wrote the celebrated Stanford University psychologist Leon Festinger [2] (PDF), in a passage that might have been referring to climate change denial—the persistent rejection, on the part of so many Americans today, of what we know about global warming and its human causes. But it was too early for that—this was the 1950s—and Festinger was actually describing a famous case study [3] in psychology.

Festinger and several of his colleagues had infiltrated the Seekers, a small Chicago-area cult whose members thought they were communicating with aliens—including one, "Sananda," who they believed was the astral incarnation of Jesus Christ. The group was led by Dorothy Martin, a Dianetics devotee who transcribed the interstellar messages through automatic writing.

Through her, the aliens had given the precise date of an Earth-rending cataclysm: December 21, 1954. Some of Martin's followers quit their jobs and sold their property, expecting to be rescued by a flying saucer when the continent split asunder and a new sea swallowed much of the United States. The disciples even went so far as to remove brassieres and rip zippers out of their trousers—the metal, they believed, would pose a danger on the spacecraft.

Festinger and his team were with the cult when the prophecy failed. First, the "boys upstairs" (as the aliens were sometimes called) did not show up and rescue the Seekers. Then December 21 arrived without incident. It was the moment Festinger had been waiting for: How would people so emotionally invested in a belief system react, now that it had been soundly refuted?

At first, the group struggled for an explanation. But then rationalization set in. A new message arrived, announcing that they'd all been spared at the last minute. Festinger summarized the extraterrestrials' new pronouncement: "The little group, sitting all night long, had spread so much light that God had saved the world from destruction." Their willingness to believe in the prophecy had saved Earth from the prophecy!

From that day forward, the Seekers, previously shy of the press and indifferent toward evangelizing, began to proselytize. "Their sense of urgency was enormous," wrote Festinger. The devastation of all they had believed had made them even more certain of their beliefs.

In the annals of denial, it doesn't get much more extreme than the Seekers. They lost their jobs, the press mocked them, and there were efforts to keep them away from impressionable young minds. But while Martin's space cult might lie at on the far end of the spectrum of human self-delusion, there's plenty to go around. And since Festinger's day, an array of new discoveries in psychology and neuroscience has further demonstrated how our preexisting beliefs, far more than any new facts, can skew our thoughts and even color what we consider our most dispassionate and logical conclusions. This tendency toward so-called "motivated reasoning [5]" helps explain why we find groups so polarized over matters where the evidence is so unequivocal: climate change, vaccines, "death panels," the birthplace and religion of the president [6] (PDF), and much else. It would seem that expecting people to be convinced by the facts flies in the face of, you know, the facts.

The theory of motivated reasoning builds on a key insight of modern neuroscience [7] (PDF): Reasoning is actually suffused with emotion (or what researchers often call "affect"). Not only are the two inseparable, but our positive or negative feelings about people, things, and ideas arise much more rapidly than our conscious thoughts, in a matter of milliseconds—fast enough to detect with an EEG device, but long before we're aware of it. That shouldn't be surprising: Evolution required us to react very quickly to stimuli in our environment. It's a "basic human survival skill," explains political scientist Arthur Lupia [8] of the University of Michigan. We push threatening information away; we pull friendly information close. We apply fight-or-flight reflexes not only to predators, but to data itself.

We apply fight-or-flight reflexes not only to predators, but to data itself.

We're not driven only by emotions, of course—we also reason, deliberate. But reasoning comes later, works slower—and even then, it doesn't take place in an emotional vacuum. Rather, our quick-fire emotions can set us on a course of thinking that's highly biased, especially on topics we care a great deal about.

Consider a person who has heard about a scientific discovery that deeply challenges her belief in divine creation—a new hominid, say, that confirms our evolutionary origins. What happens next, explains political scientist Charles Taber [9] of Stony Brook University, is a subconscious negative response to the new information—and that response, in turn, guides the type of memories and associations formed in the conscious mind. "They retrieve thoughts that are consistent with their previous beliefs," says Taber, "and that will lead them to build an argument and challenge what they're hearing."

In other words, when we think we're reasoning, we may instead be rationalizing. Or to use an analogy offered by University of Virginia psychologist Jonathan Haidt [10]: We may think we're being scientists, but we're actually being lawyers [11] (PDF). Our "reasoning" is a means to a predetermined end—winning our "case"—and is shot through with biases. They include "confirmation bias," in which we give greater heed to evidence and arguments that bolster our beliefs, and "disconfirmation bias," in which we expend disproportionate energy trying to debunk or refute views and arguments that we find uncongenial.

That's a lot of jargon, but we all understand these mechanisms when it comes to interpersonal relationships. If I don't want to believe that my spouse is being unfaithful, or that my child is a bully, I can go to great lengths to explain away behavior that seems obvious to everybody else—everybody who isn't too emotionally invested to accept it, anyway. That's not to suggest that we aren't also motivated to perceive the world accurately—we are. Or that we never change our minds—we do. It's just that we have other important goals besides accuracy—including identity affirmation and protecting one's sense of self—and often those make us highly resistant to changing our beliefs when the facts say we should.

Modern science originated from an attempt to weed out such subjective lapses—what that great 17th century theorist of the scientific method, Francis Bacon, dubbed the "idols of the mind." Even if individual researchers are prone to falling in love with their own theories, the broader processes of peer review and institutionalized skepticism are designed to ensure that, eventually, the best ideas prevail.

Scientific evidence is highly susceptible to misinterpretation. Giving ideologues scientific data that's relevant to their beliefs is like unleashing them in the motivated-reasoning equivalent of a candy store.

Our individual responses to the conclusions that science reaches, however, are quite another matter. Ironically, in part because researchers employ so much nuance and strive to disclose all remaining sources of uncertainty, scientific evidence is highly susceptible to selective reading and misinterpretation. Giving ideologues or partisans scientific data that's relevant to their beliefs is like unleashing them in the motivated-reasoning equivalent of a candy store.

Sure enough, a large number of psychological studies have shown that people respond to scientific or technical evidence in ways that justify their preexisting beliefs. In a classic 1979 experiment [12] (PDF), pro- and anti-death penalty advocates were exposed to descriptions of two fake scientific studies: one supporting and one undermining the notion that capital punishment deters violent crime and, in particular, murder. They were also shown detailed methodological critiques of the fake studies—and in a scientific sense, neither study was stronger than the other. Yet in each case, advocates more heavily criticized the study whose conclusions disagreed with their own, while describing the study that was more ideologically congenial as more "convincing."

Since then, similar results have been found for how people respond to "evidence" about affirmative action, gun control, the accuracy of gay stereotypes [13], and much else. Even when study subjects are explicitly instructed to be unbiased and even-handed about the evidence, they often fail.

And it's not just that people twist or selectively read scientific evidence to support their preexisting views. According to research by Yale Law School professor Dan Kahan [14] and his colleagues, people's deep-seated views about morality, and about the way society should be ordered, strongly predict whom they consider to be a legitimate scientific expert in the first place—and thus where they consider "scientific consensus" to lie on contested issues.

In Kahan's research [15] (PDF), individuals are classified, based on their cultural values, as either "individualists" or "communitarians," and as either "hierarchical" or "egalitarian" in outlook. (Somewhat oversimplifying, you can think of hierarchical individualists as akin to conservative Republicans, and egalitarian communitarians as liberal Democrats.) In one study, subjects in the different groups were asked to help a close friend determine the risks associated with climate change, sequestering nuclear waste, or concealed carry laws: "The friend tells you that he or she is planning to read a book about the issue but would like to get your opinion on whether the author seems like a knowledgeable and trustworthy expert." A subject was then presented with the résumé of a fake expert "depicted as a member of the National Academy of Sciences who had earned a Ph.D. in a pertinent field from one elite university and who was now on the faculty of another." The subject was then shown a book excerpt by that "expert," in which the risk of the issue at hand was portrayed as high or low, well-founded or speculative. The results were stark: When the scientist's position stated that global warming is real and human-caused, for instance, only 23 percent of hierarchical individualists agreed the person was a "trustworthy and knowledgeable expert." Yet 88 percent of egalitarian communitarians accepted the same scientist's expertise. Similar divides were observed on whether nuclear waste can be safely stored underground and whether letting people carry guns deters crime. (The alliances did not always hold. In another study [16] (PDF), hierarchs and communitarians were in favor of laws that would compel the mentally ill to accept treatment, whereas individualists and egalitarians were opposed.)

Head-on attempts to persuade can sometimes trigger a backfire effect, where people not only fail to change their minds when confronted with the facts—they may hold their wrong views more tenaciously than ever.

In other words, people rejected the validity of a scientific source because its conclusion contradicted their deeply held views—and thus the relative risks inherent in each scenario. A hierarchal individualist finds it difficult to believe that the things he prizes (commerce, industry, a man's freedom to possess a gun to defend his family [16]) (PDF) could lead to outcomes deleterious to society. Whereas egalitarian communitarians tend to think that the free market causes harm, that patriarchal families mess up kids, and that people can't handle their guns. The study subjects weren't "anti-science"—not in their own minds, anyway. It's just that "science" was whatever they wanted it to be. "We've come to a misadventure, a bad situation where diverse citizens, who rely on diverse systems of cultural certification, are in conflict," says Kahan [17].

And that undercuts the standard notion that the way to persuade people is via evidence and argument. In fact, head-on attempts to persuade can sometimes trigger a backfire effect, where people not only fail to change their minds when confronted with the facts—they may hold their wrong views more tenaciously than ever.

Take, for instance, the question of whether Saddam Hussein possessed hidden weapons of mass destruction just before the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. When political scientists Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler showed subjects fake newspaper articles [18] (PDF) in which this was first suggested (in a 2004 quote from President Bush) and then refuted (with the findings of the Bush-commissioned Iraq Survey Group report, which found no evidence of active WMD programs in pre-invasion Iraq), they found that conservatives were more likely than before to believe the claim. (The researchers also tested how liberals responded when shown that Bush did not actually "ban" embryonic stem-cell research. Liberals weren't particularly amenable to persuasion, either, but no backfire effect was observed.)

Another study gives some inkling of what may be going through people's minds when they resist persuasion. Northwestern University sociologist Monica Prasad [19] and her colleagues wanted to test whether they could dislodge the notion that Saddam Hussein and Al Qaeda were secretly collaborating among those most likely to believe it—Republican partisans from highly GOP-friendly counties. So the researchers set up a study [20] (PDF) in which they discussed the topic with some of these Republicans in person. They would cite the findings of the 9/11 Commission, as well as a statement in which George W. Bush himself denied his administration had "said the 9/11 attacks were orchestrated between Saddam and Al Qaeda."

One study showed that not even Bush's own words could change the minds of Bush voters who believed there was an Iraq-Al Qaeda link.

As it turned out, not even Bush's own words could change the minds of these Bush voters—just 1 of the 49 partisans who originally believed the Iraq-Al Qaeda claim changed his or her mind. Far more common was resisting the correction in a variety of ways, either by coming up with counterarguments or by simply being unmovable:

Interviewer: [T]he September 11 Commission found no link between Saddam and 9/11, and this is what President Bush said. Do you have any comments on either of those?

Respondent: Well, I bet they say that the Commission didn't have any proof of it but I guess we still can have our opinions and feel that way even though they say that.

The same types of responses are already being documented on divisive topics facing the current administration. Take the "Ground Zero mosque." Using information from the political myth-busting site FactCheck.org [21], a team at Ohio State presented subjects [22] (PDF) with a detailed rebuttal to the claim that "Feisal Abdul Rauf, the Imam backing the proposed Islamic cultural center and mosque, is a terrorist-sympathizer." Yet among those who were aware of the rumor and believed it, fewer than a third changed their minds.

A key question—and one that's difficult to answer—is how "irrational" all this is. On the one hand, it doesn't make sense to discard an entire belief system, built up over a lifetime, because of some new snippet of information. "It is quite possible to say, 'I reached this pro-capital-punishment decision based on real information that I arrived at over my life,'" explains Stanford social psychologist Jon Krosnick [23]. Indeed, there's a sense in which science denial could be considered keenly "rational." In certain conservative communities, explains Yale's Kahan, "People who say, 'I think there's something to climate change,' that's going to mark them out as a certain kind of person, and their life is going to go less well."

This may help explain a curious pattern Nyhan and his colleagues found when they tried to test the fallacy [6] (PDF) that President Obama is a Muslim. When a nonwhite researcher was administering their study, research subjects were amenable to changing their minds about the president's religion and updating incorrect views. But when only white researchers were present, GOP survey subjects in particular were more likely to believe the Obama Muslim myth than before. The subjects were using "social desirabililty" to tailor their beliefs (or stated beliefs, anyway) to whoever was listening.

Which leads us to the media. When people grow polarized over a body of evidence, or a resolvable matter of fact, the cause may be some form of biased reasoning, but they could also be receiving skewed information to begin with—or a complicated combination of both. In the Ground Zero mosque case, for instance, a follow-up study [24] (PDF) showed that survey respondents who watched Fox News were more likely to believe the Rauf rumor and three related ones—and they believed them more strongly than non-Fox watchers.

Okay, so people gravitate toward information that confirms what they believe, and they select sources that deliver it. Same as it ever was, right? Maybe, but the problem is arguably growing more acute, given the way we now consume information—through the Facebook links of friends, or tweets that lack nuance or context, or "narrowcast [25]" and often highly ideological media that have relatively small, like-minded audiences. Those basic human survival skills of ours, says Michigan's Arthur Lupia, are "not well-adapted to our information age."

A predictor of whether you accept the science of global warming? Whether you're a Republican or a Democrat.

If you wanted to show how and why fact is ditched in favor of motivated reasoning, you could find no better test case than climate change. After all, it's an issue where you have highly technical information on one hand and very strong beliefs on the other. And sure enough, one key predictor of whether you accept the science of global warming is whether you're a Republican or a Democrat. The two groups have been growing more divided in their views about the topic, even as the science becomes more unequivocal.

So perhaps it should come as no surprise that more education doesn't budge Republican views. On the contrary: In a 2008 Pew survey [26], for instance, only 19 percent of college-educated Republicans agreed that the planet is warming due to human actions, versus 31 percent of non-college educated Republicans. In other words, a higher education correlated with an increased likelihood of denying the science on the issue. Meanwhile, among Democrats and independents, more education correlated with greater acceptance of the science.

Other studies have shown a similar effect: Republicans who think they understand the global warming issue best are least concerned about it; and among Republicans and those with higher levels of distrust of science in general, learning more about the issue doesn't increase one's concern about it. What's going on here? Well, according to Charles Taber and Milton Lodge of Stony Brook, one insidious aspect of motivated reasoning is that political sophisticates are prone to be more biased than those who know less about the issues. "People who have a dislike of some policy—for example, abortion—if they're unsophisticated they can just reject it out of hand," says Lodge. "But if they're sophisticated, they can go one step further and start coming up with counterarguments." These individuals are just as emotionally driven and biased as the rest of us, but they're able to generate more and better reasons to explain why they're right—and so their minds become harder to change.

That may be why the selectively quoted emails of Climategate were so quickly and easily seized upon by partisans as evidence of scandal. Cherry-picking is precisely the sort of behavior you would expect motivated reasoners to engage in to bolster their views—and whatever you may think about Climategate, the emails were a rich trove of new information upon which to impose one's ideology.

Climategate had a substantial impact on public opinion, according to Anthony Leiserowitz [27], director of the Yale Project on Climate Change Communication [28]. It contributed to an overall drop in public concern about climate change and a significant loss of trust in scientists. But—as we should expect by now—these declines were concentrated among particular groups of Americans: Republicans, conservatives, and those with "individualistic" values. Liberals and those with "egalitarian" values didn't lose much trust in climate science or scientists at all. "In some ways, Climategate was like a Rorschach test," Leiserowitz says, "with different groups interpreting ambiguous facts in very different ways."

Is there a case study of science denial that largely occupies the political left? Yes: the claim that childhood vaccines are causing an epidemic of autism.

So is there a case study of science denial that largely occupies the political left? Yes: the claim that childhood vaccines are causing an epidemic of autism. Its most famous proponents are an environmentalist (Robert F. Kennedy Jr. [29]) and numerous Hollywood celebrities (most notably Jenny McCarthy [30] and Jim Carrey). The Huffington Post gives a very large megaphone to denialists. And Seth Mnookin [31], author of the new book The Panic Virus [32], notes that if you want to find vaccine deniers, all you need to do is go hang out at Whole Foods.

Vaccine denial has all the hallmarks of a belief system that's not amenable to refutation. Over the past decade, the assertion that childhood vaccines are driving autism rates has been undermined [33] by multiple epidemiological studies—as well as the simple fact that autism rates continue to rise, even though the alleged offending agent in vaccines (a mercury-based preservative called thimerosal) has long since been removed.

Yet the true believers persist—critiquing each new study that challenges their views, and even rallying to the defense of vaccine-autism researcher Andrew Wakefield, after his 1998 Lancet paper [34]—which originated the current vaccine scare—was retracted and he subsequently lost his license [35] (PDF) to practice medicine. But then, why should we be surprised? Vaccine deniers created their own partisan media, such as the website Age of Autism, that instantly blast out critiques and counterarguments whenever any new development casts further doubt on anti-vaccine views.

It all raises the question: Do left and right differ in any meaningful way when it comes to biases in processing information, or are we all equally susceptible?

There are some clear differences. Science denial today is considerably more prominent on the political right—once you survey climate and related environmental issues, anti-evolutionism, attacks on reproductive health science by the Christian right, and stem-cell and biomedical matters. More tellingly, anti-vaccine positions are virtually nonexistent among Democratic officeholders today—whereas anti-climate-science views are becoming monolithic among Republican elected officials.

Some researchers have suggested that there are psychological differences between the left and the right that might impact responses to new information—that conservatives are more rigid and authoritarian, and liberals more tolerant of ambiguity. Psychologist John Jost of New York University has further argued that conservatives are "system justifiers": They engage in motivated reasoning to defend the status quo.

This is a contested area, however, because as soon as one tries to psychoanalyze inherent political differences, a battery of counterarguments emerges: What about dogmatic and militant communists? What about how the parties have differed through history? After all, the most canonical case of ideologically driven science denial is probably the rejection of genetics in the Soviet Union, where researchers disagreeing with the anti-Mendelian scientist (and Stalin stooge) Trofim Lysenko were executed, and genetics itself was denounced as a "bourgeois" science and officially banned.

The upshot: All we can currently bank on is the fact that we all have blinders in some situations. The question then becomes: What can be done to counteract human nature itself?

We all have blinders in some situations. The question then becomes: What can be done to counteract human nature?

Given the power of our prior beliefs to skew how we respond to new information, one thing is becoming clear: If you want someone to accept new evidence, make sure to present it to them in a context that doesn't trigger a defensive, emotional reaction.

This theory is gaining traction in part because of Kahan's work at Yale. In one study [36], he and his colleagues packaged the basic science of climate change into fake newspaper articles bearing two very different headlines—"Scientific Panel Recommends Anti-Pollution Solution to Global Warming" and "Scientific Panel Recommends Nuclear Solution to Global Warming"—and then tested how citizens with different values responded. Sure enough, the latter framing made hierarchical individualists much more open to accepting the fact that humans are causing global warming. Kahan infers that the effect occurred because the science had been written into an alternative narrative that appealed to their pro-industry worldview.

You can follow the logic to its conclusion: Conservatives are more likely to embrace climate science if it comes to them via a business or religious leader, who can set the issue in the context of different values than those from which environmentalists or scientists often argue. Doing so is, effectively, to signal a détente in what Kahan has called a "culture war of fact." In other words, paradoxically, you don't lead with the facts in order to convince. You lead with the values—so as to give the facts a fighting chance.

Source URL: http://motherjones.com/politics/2011/03/denial-science-chris-mooney

Links:

[1] http://motherjones.com/environment/2011/04/history-of-climategate

[2] https://motherjones.com/files/lfestinger.pdf

[3] http://www.powells.com/biblio/61-9781617202803-1

[4] http://motherjones.com/environment/2011/04/field-guide-climate-change-skeptics

[5] http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2270237

[6] http://www-personal.umich.edu/~bnyhan/obama-muslim.pdf

[7] https://motherjones.com/files/descartes.pdf

[8] http://www-personal.umich.edu/~lupia/

[9] http://www.stonybrook.edu/polsci/ctaber/

[10] http://people.virginia.edu/~jdh6n/

[11] https://motherjones.com/files/emotional_dog_and_rational_tail.pdf

[12] http://synapse.princeton.edu/~sam/lord_ross_lepper79_JPSP_biased-assimilation-and-attitude-polarization.pdf

[13] http://psp.sagepub.com/content/23/6/636.abstract

[14] http://www.law.yale.edu/faculty/DKahan.htm

[15] https://motherjones.com/files/kahan_paper_cultural_cognition_of_scientific_consesus.pdf

[16] http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1095&context=fss_papers

[17] http://seagrant.oregonstate.edu/blogs/communicatingclimate/transcripts/Episode_10b_Dan_Kahan.html

[18] http://www-personal.umich.edu/~bnyhan/nyhan-reifler.pdf

[19] http://www.sociology.northwestern.edu/faculty/prasad/home.html

[20] http://sociology.buffalo.edu/documents/hoffmansocinquiryarticle_000.pdf

[21] http://www.factcheck.org/

[22] http://www.comm.ohio-state.edu/kgarrett/FactcheckMosqueRumors.pdf

[23] http://communication.stanford.edu/faculty/krosnick/

[24] http://www.comm.ohio-state.edu/kgarrett/MediaMosqueRumors.pdf

[25] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narrowcasting

[26] http://people-press.org/report/417/a-deeper-partisan-divide-over-global-warming

[27] http://environment.yale.edu/profile/leiserowitz/

[28] http://environment.yale.edu/climate/

[29] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/robert-f-kennedy-jr-and-david-kirby/vaccine-court-autism-deba_b_169673.html

[30] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jenny-mccarthy/vaccine-autism-debate_b_806857.html

[31] http://sethmnookin.com/

[32] http://www.powells.com/biblio/1-9781439158647-0

[33] http://discovermagazine.com/2009/jun/06-why-does-vaccine-autism-controversy-live-on/article_print

[34] http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140673697110960/fulltext

[35] http://www.gmc-uk.org/Wakefield_SPM_and_SANCTION.pdf_32595267.pdf

[36] http://www.scribd.com/doc/3446682/The-Second-National-Risk-and-Culture-Study-Making-Sense-of-and-Making-Progress-In-The-American-Culture-War-of-Fact

And some funnies:

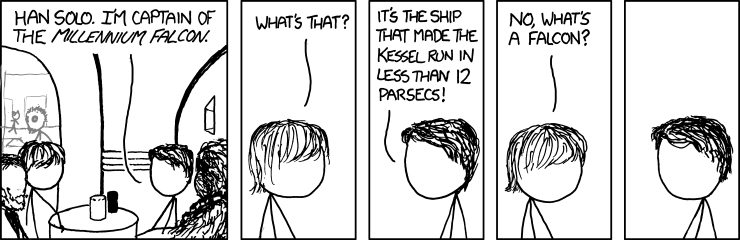

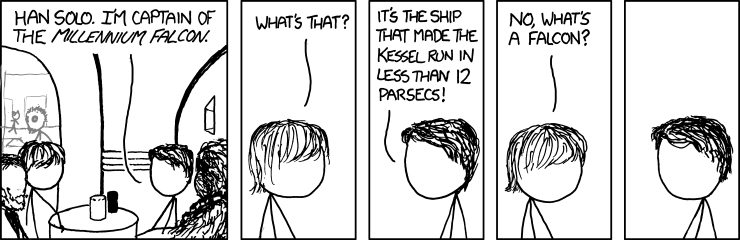

XKCD + Star Wars:

Probably the best Dinosaur comic ever:

First of all, I'm not a big fan of Tumblr - it often seems to be the worst kind of social media: no original content or even your own thoughts, just reposting, BUT, these, these I approve of:

Dads are the Original Hipster

And Hipster Animals:

Then, some feminism related links:

Poor Jane’s Almanac

By JILL LEPORE

The New York Times

Cambridge, Mass.

THE House Budget Committee chairman, Paul D. Ryan, a Republican from Wisconsin, announced his party’s new economic plan this month. It’s called “The Path to Prosperity,” a nod to an essay Benjamin Franklin once wrote, called “The Way to Wealth.”

Franklin, who’s on the $100 bill, was the youngest of 10 sons. Nowhere on any legal tender is his sister Jane, the youngest of seven daughters; she never traveled the way to wealth. He was born in 1706, she in 1712. Their father was a Boston candle-maker, scraping by. Massachusetts’ Poor Law required teaching boys to write; the mandate for girls ended at reading. Benny went to school for just two years; Jenny never went at all.

Their lives tell an 18th-century tale of two Americas. Against poverty and ignorance, Franklin prevailed; his sister did not.

At 17, he ran away from home. At 15, she married: she was probably pregnant, as were, at the time, a third of all brides. She and her brother wrote to each other all their lives: they were each other’s dearest friends. (He wrote more letters to her than to anyone.) His letters are learned, warm, funny, delightful; hers are misspelled, fretful and full of sorrow. “Nothing but troble can you her from me,” she warned. It’s extraordinary that she could write at all.

“I have such a Poor Fackulty at making Leters,” she confessed.

He would have none of it. “Is there not a little Affectation in your Apology for the Incorrectness of your Writing?” he teased. “Perhaps it is rather fishing for commendation. You write better, in my Opinion, than most American Women.” He was, sadly, right.

She had one child after another; her husband, a saddler named Edward Mecom, grew ill, and may have lost his mind, as, most certainly, did two of her sons. She struggled, and failed, to keep them out of debtors’ prison, the almshouse, asylums. She took in boarders; she sewed bonnets. She had not a moment’s rest.

And still, she thirsted for knowledge. “I Read as much as I Dare,” she confided to her brother. She once asked him for a copy of “all the Political pieces” he had ever written. “I could as easily make a collection for you of all the past parings of my nails,” he joked. He sent her what he could; she read it all. But there was no way out.

They left very different paper trails. He wrote the story of his life, stirring and wry — the most important autobiography ever written. She wrote 14 pages of what she called her “Book of Ages.” It isn’t an autobiography; it is, instead, a litany of grief, a history, in brief, of a life lived rags to rags.

It begins: “Josiah Mecom their first Born on Wednesday June the 4: 1729 and Died May the 18-1730.” Each page records another heartbreak. “Died my Dear & Beloved Daughter Polly Mecom,” she wrote one dreadful day, adding, “The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away oh may I never be so Rebelious as to Refuse Acquesing & saying from my hart Blessed be the Name of the Lord.”

Jane Mecom had 12 children; she buried 11. And then, she put down her pen.

Today, two and a half centuries later, the nation’s bookshelves sag with doorstop biographies of the founders; Tea Partiers dressed as Benjamin Franklin call for an end to social services for the poor; and the “Path to Prosperity” urges a return to “America’s founding ideals of liberty, limited government and equality under the rule of law.” But the story of Jane Mecom is a reminder that, especially for women, escaping poverty has always depended on the opportunity for an education and the ability to control the size of their families.

The latest budget reduces financing for Planned Parenthood, for public education and even for the study of history. At one point in the budget discussion, all money for Teaching American History, a federal program offering training to K-12 history teachers, was eliminated. Are we never to study the book of ages?

On July 4, 1786, when Jane Mecom was 74, she thought about the path to prosperity. It was the nation’s 10th birthday. She had been reading a book by the Englishman Richard Price. “Dr Price,” she wrote to her brother, “thinks Thousands of Boyles Clarks and Newtons have Probably been lost to the world, and lived and died in Ignorance and meanness, merely for want of being Placed in favourable Situations, and Injoying Proper Advantages.” And then she reminded her brother, gently, of something that he knew, and she knew, about the world in which they lived: “Very few is able to beat thro all Impedements and Arive to any Grat Degre of superiority in Understanding.”

That world was changing. In 1789, Boston for the first time, allowed girls to attend public schools. The fertility rate began declining. The American Revolution made possible a new world, a world of fewer obstacles, a world with a promise of equality. That required — and still requires — sympathy.

Benjamin Franklin died in Philadelphia in 1790, at the age of 84. In his will, he left Jane the house in which she lived. And then he made another bequest, more lasting: he gave one hundred pounds to the public schools of Boston.

Jane Mecom died in that house in 1794. Later, during a political moment much like this one, when American politics was animated by self-serving invocations of the founders, her house was demolished to make room for a memorial to Paul Revere.

Jill Lepore, a professor of American history at Harvard, is the author of “The Whites of Their Eyes: The Tea Party’s Revolution and the Battle Over American History.”

Dallas Sports Columnist Displeased With Pitcher’s Decision To Do A Totally Normal Thing

It can be hard to tell that Dallas Observer sports blogger Richie Whitt is a sports blogger, since his professional blog, the one that is actually hosted on Village Voice servers, largely consists of pictures of women in various states of undress and reflections on recent Korn performances, so you could be forgiven for wondering where the hell he thinks he gets off shitting on Texas Rangers pitcher Colby Lewis for having the gall to miss a start in favor of attending the birth of his second child.

I mean, my first question was, what is Richie Whitt doing writing about sports, anyway? Is there not a wet t-shirt somewhere in the whole of suburban North Texas that needs his undivided attention?

Apparently not. No, when Whitt heard that Colby Lewis skipped a game, well, this:

In Game 2, Colby Lewis is scheduled to start after missing his last regular turn in the rotation because — I’m not making this up — his wife, Jenny, was giving birth in California. To the couple’s second child.

That’s right, folks. If you can believe it, this guy attended the birth of his child. Take a moment to collect yourselves if you must. I know news like this can be hard to process. Ok? Ok.

And lest you think that Whitt was just joking, I invite you to read further, wherein Whitt doesn’t really joke at all but just talks about how hard it is for him to wrap his mind around the idea of taking a day off to see your kid born.

Don’t have kids of my own but I raised a step-son for eight years. I know all about sacrifice and love and how great children are.

But a pitcher missing one of maybe 30 starts? And it’s all kosher because of Major League Baseball’s new paternity leave rule?

Follow me this way to some confusion.

Imagine if Jason Witten missed a game to attend the birth of a child. It’s just, I dunno, weird. Wrong even.

See, it’s not that childless, single Whitt doesn’t know all about children and family sacrifice, it’s just that another dude choosing a different path than his is too hard for him to understand, and therefore wrong. No doubt the Gender Police have given Whitt some kind of very meaningful commendation (gilt mud tires, maybe!) and are preparing for quite the promotion ceremony.

Here’s where shit gets real: as the confused and disappointed Whitt noted, Colby Lewis is the first MLB baseball player to ever go on the league’s paternity leave list. This is not a small deal. This is a huge deal. This is a deal where a major sports operation moves from saying, hey dudes, we will pay you gazillions of dollars to chase a ball around a field and kids will look up to you for that as a role model, to saying hey dudes, with our express permission, how about you go be a father if you want to, because that is a good thing to do, that is also a role model thing to do. And Colby Lewis took them up on that. He decided that being a dad is important to him. And he went and was a dad and a husband and a partner.

And what’s more: he came back to work and is still a pretty fucking good baseball player.

So we can shrug off Whitt and say he’s just being a shit-stirring media personality who thinks any attention is good attention, which I am definitely doing, and which I think is a reasonable thing to do. But we need to go a step further and call out Whitt for using his shock-jock personality to perpetuate a system of toxic masculinity wherein men are only real dudes if they don’t do too much of that being-a-human-being shit, like trying to physically and emotionally support their families, witness once-in-a-lifetime moments and demonstrate that there’s more to life than a paycheck. Toxic masculinity, gender policing and shaming doesn’t just hurt women. Doesn’t just hurt men. Hurts everyone. Hurts families. Hurts people, all people, who deserve to not be pigeonholed and socially pressured into any one kind of behavior based on the junk in their drawers.

With this column, Whitt really hits the Toxic Masculinity Trifecta: ignorance (caveman too stupid to understand things other than sports/beer), fear (caveman cowed by freaky, unwelcoming ladybits and operations thereof) and dick-centricity (caveman judge value of all behavior in light of adherence to other socially constructed, traditionally male behavior). But hey, no doubt Whitt is pretty pleased at all the attention this is getting, not to mention the page views, because hey, page views you guys! It’s basically like thinking up a new cat meme! Victimless crime!

Except this kind of horsesassery isn’t a victimless crime at all. I don’t know if you guys look forward to this, or if Richie Whitt looks forward to this, but I do look forward to it: a day when those who have the microphone do not casually and ignorantly reinforce systems of gendered oppression that have been fucking up people’s shit for an awfully long time. Or maybe I’m wrong. Maybe being a father is the worst, and mocking men for doing absolutely, totally hetero-normal family stuff is super classy and awesome. I may have missed that memo because I was busy being parented by a loving father before growing up to watch many of my guy friends become great parents, because again, that is a normal and acceptable thing dudes do.

Of course, it’s interesting to observe the point at which Whitt, champion of toxic masculinity if ever there was one, felt it was reasonable and/or funny to call it “wrong” when a guy has demonstrably done the most heteronormative thing possible, which is to make a baby with a lady. Whitt doesn’t mind kids and family, ya know, he’s totally cool with that–it’s just that he wants to make sure the kids and family don’t upset some abstract image of Studly Professional Athlete, who is the epitome of manliness and would never let anything as silly–and unmanly–as parenting get in the way of actual priorities, like a baseball game. (And an individual baseball game as priority is up for serious debate, anyway, so go read Jason Heid’s post on Frontburner for more on why it’s not that big of a freaking deal if Lewis misses one game out of 30.)

So it’s really very simple: by choosing his family over his job, Colby Lewis is not performing masculinity properly, and that scares the shit out of people who have invested their entire careers, even their whole identities, in reinforcing said masculinity. What do I mean when I say a super studly professional athlete is not performing masculinity properly? I mean this: Colby Lewis’ act of choosing to be at the birth of his kid rather than starting as pitcher in a major league baseball game is a direct and public challenge to the patriarchal norm which dictates that women will be the ones to make career sacrifices, full stop. < / getting all women’s studies 101 on your asses >

Now, Whitt and his fans, one or both or all of whom I expect to turn up here in the comments section at any moment (oh, how I hope to hear a new sandwich-kitchen-stove joke, or perhaps a lengthy inquiry into whether I am fat, ugly or slutty!) probably think this all sounds like a bunch of feminist hoo-hah. It it totally is. Because feminism is for dudes, y’all. Richie Whitt just proved it.

Academia related links:

April 24, 2011

Paranoid? You Must Be a Grad Student

By Don Troop

Memo to grad students: Just because you're paranoid doesn't mean they're not about to give you a Ph.D.

A mild case of paranoia might even help you navigate the tricky path to that terminal degree, says Roderick M. Kramer, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford University's Graduate School of Business.

It's an academic cliché that graduate students are paranoid, but Mr. Kramer has actually crafted a linear model to explain it. The model depicts how factors common to the graduate-school experience—like being a newcomer unsure of your standing, and knowing that you're being sized up constantly—can ultimately induce social paranoia, a heightened sensitivity to what you imagine others might be thinking about you.

"That self-consciousness translates into a tendency to be extra vigilant and maybe overprocess information on how you're treated," Mr. Kramer says. (He published his model in a 1998 paper, "Paranoid Cognition in Social Systems.")

To be clear, he is not talking about clinical paranoia, an illness he studied at the University of California at Los Angeles under the psychiatrist Kenneth Colby, who had developed a computerized paranoid schizophrenic called PARRY. And Mr. Kramer, who has written extensively on the social psychology of trust and distrust, doesn't regard social paranoia as a pejorative term, either.

"It's meant to be almost a playful label to help people remember the consequences of being in these situations," he says.

Not only does he know what you're thinking, but he also knows why. Roderick M. Kramer has developed a linear model to explain the type of social paranoia common to graduate students.

Academe, says the cartoonist Jorge Cham, is an ego-driven industry where perception is everything and weakness is perceived as a character flaw.

Mr. Cham abandoned his own academic career as a robotics researcher six years ago to draw his comic-strip parody of grad-school life, Piled Higher and Deeper.

"It's competitive, so people are very afraid of admitting that they're having trouble with their research, or that they're having trouble getting data, or that maybe they need to rethink their hypotheses," says Mr. Cham. That often means that the people best positioned to help a grad student resolve a particular dilemma—the adviser and members of the cohort—are the last ones the student will go to for help.

In spite of the accomplishments listed on their CV's, Mr. Cham says that grad students sometimes pull him aside and privately admit feeling like "they're somehow not smart enough or that they're fooling people—that they feel like impostors."

The students interviewed for this article raised that theme more than once. Anxiety about their standing seemed to vary depending on details like gender, field of study, fellow students' collegiality, and the adviser's attentiveness. The biggest variable, of course, was the student.

"I've never presented a project that I haven't felt like my peers or my faculty would find outstanding because I'm so nervous about being judged harshly," says a graduate student in anthropology at a large state university in the South. Though her adviser is warm and supportive and her fellow-grad students are friendly, she routinely hears them criticizing presentations by scholars from other universities after academic conferences. "The last thing you want to do is be on the other end of that stick," says the student, who describes scholarly research and presentation as an "academic performance" with its own precise language and exacting standards.

And as a woman in science she is up against what Mr. Kramer says is one of the primary antecedents to grad-student paranoia: the feeling of being socially distinct—a token. "I'm constantly curious about whether I'm being taken seriously," she says. "I'm very aware of hemlines, how much my neckline plummets, if I'm wearing too much makeup."

Like most graduate students interviewed for this article, she agreed to speak only if guaranteed anonymity. Does that sound a little paranoid? Mr. Kramer might deem it wise. A mild social paranoia can actually be helpful, he says, because it can trigger the types of "prudent and adaptive" behaviors that the anthropology student described, like adjusting your speech or appearance to fit in. It might also cause you not to want a reporter to use your name when you reveal that sometimes you feel a little paranoid.

Paranoia has its Pluses

Bradley Ricca earned his doctorate in 2003 from Case Western Reserve University, where today he is a lecturer in English. He recalls experiencing his own adaptive response to grad-student paranoia while preparing for his comprehensive exams. Mr. Ricca, who had been given two questions to study, got word that a friend who was also taking the exams was poised to set the curve.

"I heard that he had not only already written extensive outlines and copy for his answers, but he had footnoted them as well," Mr. Ricca wrote in an e-mail describing the incident. "I froze in my Doc Martens."

Mr. Ricca skipped sleep for nearly a week, writing out his answers and footnoting them. Both men passed their comps, and while Mr. Ricca never did find out whether the rumor about his friend was true, he credits "the paranoia inherent in English departments" with motivating him to study harder.

"English studies seems, to me, a culture laced with paranoia," Mr. Ricca says. "Where are the jobs? Where is the funding? What are we doing this decade?"

People who work in creative programs often suffer the worst from social paranoia, says Mr. Kramer, who began his own academic career as an English major aspiring to publish novels and screenplays.

"The more subjective the enterprise, the more uncertainty about the evaluative standard, the easier it is to overprocess information," he says. "You don't have that objective reference."

One former graduate student in a "cutthroat writing program" sums it up: "When someone criticizes your poem, you think, 'Why do they hate me so much?'"

Mr. Kramer says it's up to good doctoral advisers to minimize that dysfunctional suspicion. "They should stay in touch with their students. They should give them regular feedback that lets them know where they stand—not false feedback to make them unduly optimistic—but realistic feedback."

A female graduate of a different writing program—one where the cohort was much younger than she was and the faculty largely male and unsupportive—credits her survival to valuable mentoring from a new (male) faculty member who wasn't part of the old guard. She also followed the advice of a more senior grad student: "Invest your ego somewhere else and find some support system that's separate from this program—your family, your lover, or whoever."

In her case, the woman bonded with a fellow student who was also in her late 20s, and the two women helped each other gauge when their peers' criticisms were valid and when they were simply rooted in competition.

Such social support systems are a "very adaptive, healthy strategy that reduces uncertainty about your standing," Mr. Kramer says.

But a graduate student in clinical psychology at a public university in the Northeast says he's seen problems result when people try to function as both confidant and classmate.

"Business and pleasure often get mixed together when you're working 80 hours a week and you spend 90 percent of your waking moments with the same people," he says. "You really rely on these people to satisfy multiple roles, and trying to maintain these things certainly can ramp up the anxiety."

Also muddying his department's mental-health waters, he says, is that clinical psychologists sometimes take on some of the characteristics of the patients they work with.

"There might be a bit of an overrepresentation in terms of how people tend to express themselves, just given the content of what we study," he says.

"We tend to adopt the mind-set of those we're trying to conceptualize."

Adding to the anxiety, he says, are the same things that his peers in other disciplines worry about, like whether they're successfully evolving from students into professionals, and whether the gamble of grad school will pay off financially.

"I'm aware of people experiencing symptoms of paranoia or this feeling of disassociating when they're under heightened anxiety for prolonged periods of time, which seems to be the definition, in many ways, of graduate school," he says.

Sometimes, he says, the pressure students feel to demonstrate their mastery of the subject to professors comes at the expense of relationships with their peers. He's even seen students confront one another for talking too loudly or in other ways overshadowing their classmates.

A medical student at the same Northeast institution admits that he and others spend a disproportionate amount of time mulling how to impress their professors in hopes of getting favorable letters of recommendation for their residency applications.

On rotations they may work with a particular professor for only three or four weeks, a short time "to demonstrate that we're personable and that we have the knowledge they demand from us," he says. Grad students feel they must keep themselves at the fore of their professors' minds.